The Drop

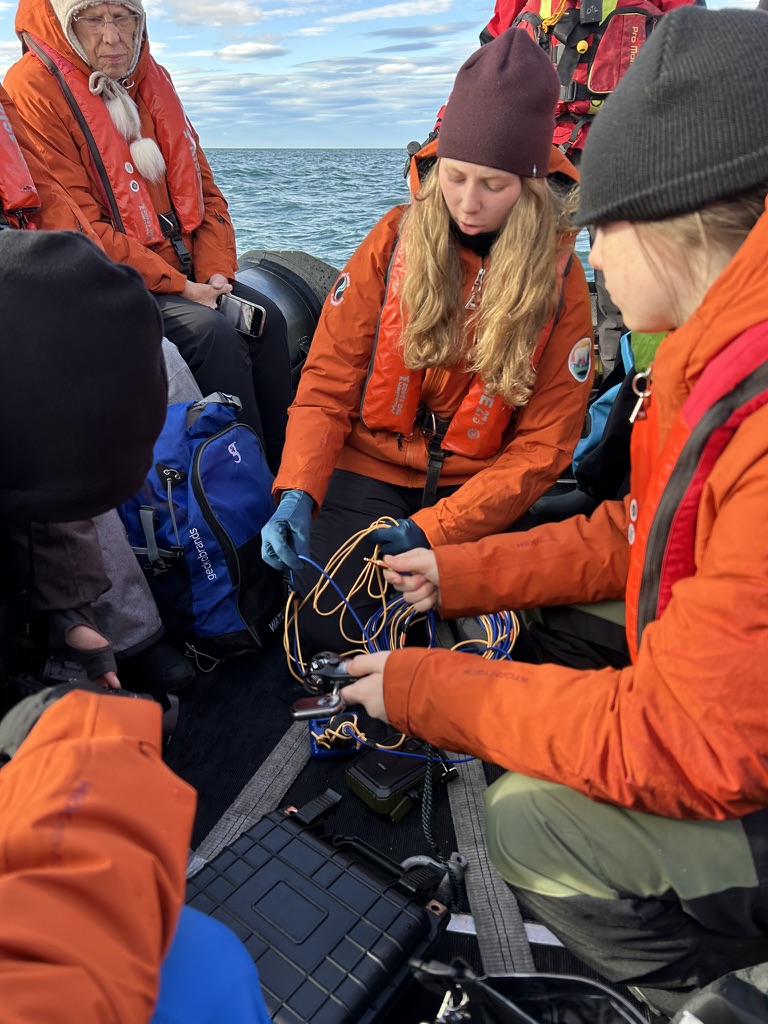

Deploying a hydrophone in Arctic waters for the first time felt a little like sending a message in a bottle—except this bottle was expensive, carefully engineered, and had to survive the crushing weight of 10 meters of water. The team peered off the side of the zodiac; anxious, excited, and curious, straining our ears against the biting cold of the wind for that first telltale crackle of noise as the hydrophone broke the surface of the water. Slowly and deliberately, hand over hand, meter over meter, we called out to each other as it was lowered into the sea: “One, two, three . . . let’s go to eight on this first drop and see what we get.”

Almost immediately, there was a hush among us. We were no longer casual observers, explorers out on expeditions on the water’s surface. We were scientists, capturing data by connecting to the world below it.

To truly capture the experience of deploying this hydrophone, we must first rewind the tapes a bit. Weeks and months of countless emails, phone calls, meetings, back and forth, dead ends, and close calls left Cristie Ledon Moore, the Seabirds’ Director of Science, and me holding our breath hoping it would work out. Sounds like a great mystery novel, right? Wrong. This was the experience of learning how to procure diplomatic certification to legally deploy our hydrophone to capture acoustic data—and small water samples—in international waters. We quickly found out that collecting data at sea isn’t just about gear and grit; it’s about paperwork. Lots of it. Thankfully, we teamed up with the best of the best at the US State Department. For the purpose of this post, we’ll call her G; she held our hand from start to finish, making sure all of our applications, documentation, and certifications were properly in place.

To do this work responsibly, we had to write detailed protocols outlining exactly how we would collect and store the information we captured. We had to explain precisely where we’d be collecting these samples, which equipment we’d be using, who would be present, who would have access to this data, how and where it would be stored, and our timeframe for ensuring each government—of the samples we’d be collecting—had access to it in a timely manner.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Reach out to the US Consulate and the Department of State for guidance.

- Submit applications explaining what we’re doing, where, why, and how it will be used.

- Email back and forth with G—sometimes daily—about how close we’d be to shorelines, national parks, answering questions the different governments posed, and finally submitting.

- Wait for the approval.

- Celebrate when it came through!

This part of expedition life isn’t glamorous, it’s essential. Permits ensure the work is legal and respected by the countries whose waters we’re entering. Peering off the side of the zodiac into the emerald green waters of Greenland, watching the hydrophone drop meter by meter through the water column, suddenly made these minor administrative frustrations and months of tedious paperwork completely justified. I watched people on our zodiac, many of whom had never seen a hydrophone in person, hold one in their hands, drop it through cracks in the ice, and listen to the sounds of life—from the movement of water to the popping of ancient air bubbles escaping icebergs. It was labor-intensive, yes, but knowing that this data would be available to scientists, musicians, artists, students, and curious minds at home, made every bit of it worthwhile.

-Ash xo